How Hooker found his boogie: a rhythmic analysis of a classicgroove フッカーはいかにして自分のブギを見つけたのか:クラシックなグルーヴのリズム分析

FERNANDO BENADON と TED GIOIA 氏の論文の翻訳です。

http://www.fernandobenadon.com/uploads/1/8/4/2/18429773/how_hooker_found_his_boogie.pdf

Abstract

要旨

This article closely analyses the rhythmic components in John Lee Hooker’s boogie. We show how Hooker recasts a signature riff from a ternary to a binary beat subdivision, paving the way for the triple-to-duple shift that characterised mid-century American popular music.

本稿は、ジョン・リー・フッカーのブギにおけるリズム要素を詳細に分析する。フッカーが、三分割の拍下位構造に基づく代表的なリフを二分割のビートへと再構成している過程を示し、それが20世紀中頃のアメリカ大衆音楽を特徴づけた「三拍から二拍への転換」への道を切り開いたことを明らかにする。

Further, we attribute the boogie’s ‘hypnotic’ feel to two psychoacoustic phenomena: stream segregation and temporal order misjudgement. Stream segregation occurs when the musical surface is divided by the listener into two or more auditory entities (streams), usually as a result of timbral and registral contrasts.

さらに本稿では、このブギがもつ「催眠的」と形容される感覚を、ストリーム分離と時間順序の誤判断という二つの心理音響学的現象に帰属させる。ストリーム分離とは、音色や音域の対比などを手がかりとして、聴取者が音楽表面を二つ以上の聴覚的存在(ストリーム)に分割して知覚する現象である。

In Hooker’s case, these contrasts occur between the guitar groove’s downbeats and upbeats, whose extreme proximity also blurs their temporal order. These expressive effects are complemented by global and gradual accelerandos that envelop Hooker’s early performances.

フッカーの場合、こうした対比はギター・グルーヴにおけるダウンビートとアップビートの間に生じており、両者が極めて近接しているため、その時間的な前後関係も曖昧になる。こうした表現効果は、フッカーの初期の演奏全体を包み込むように進行する、全体的かつ緩やかなアッチェレランドによって、さらに補完されている。

Introduction

序論

John Lee Hooker’s recording of ‘Boogie Chillen’ in November 1948 stands out as one of the greatest, and most unlikely, hits in the history of blues music. Composers of popular songs often claim that a ‘hook’ is essential to a successful recording, so if ‘Boogie Chillen’ had a hook, surely it was a rhythmic one. The song’s melodic and harmonic content is practically nil. It is mostly an up-tempo talking blues, spoken or semi-spoken in a type of blues recitative.

ジョン・リー・フッカーが1948年11月に録音した『Boogie Chillen』は、ブルース音楽の歴史において、最も偉大であると同時に、最も意外性のあるヒット作の一つとして際立っている。ポピュラー音楽の作曲家たちはしばしば、成功する録音には「フック」が不可欠だと語るが、もし『Boogie Chillen』にフックがあるとすれば、それは間違いなくリズム的なものだろう。この曲の旋律的・和声的内容は、ほとんど存在しないと言ってよい。楽曲の大半は、アップテンポのトーキング・ブルースであり、ブルース的レチタティーヴォの一種として、語り、あるいは半ば語りのように演じられている。

Nor did Hooker rely on clever arrangements and slick studio effects – so common during these post-war years – to secure a hit song. He performed solo, with only his guitar and stomping foot for accompaniment. Yet this stark, idiosyncratic song proved to be a runaway hit. ‘Boogie Chillen’ climbed to the top spot in Billboard’s R&B charts, and propelled Hooker from obscurity to fame almost overnight. It is hard to imagine the lyrics as the source of the song’s appeal; they are simple, almost simple-minded, little more than a series of short declamatory sentences such as:

この時代の戦後ポピュラー音楽において一般的であったような、巧妙なアレンジや洗練されたスタジオ効果に、フッカーはまったく頼っていなかった。彼はギター一本と足踏みだけを伴奏に、完全なソロ演奏を行っている。それにもかかわらず、この簡素で強烈に個性的な楽曲は、予想外の大ヒットとなった。『Boogie Chillen』はBillboardのR&Bチャートで首位に上り詰め、フッカーをほとんど一夜にして無名の存在からスターへと押し上げた。この曲の魅力の源泉を歌詞に求めるのは難しい。歌詞はきわめて単純で、ほとんど素朴と言ってよいほどであり、次のような短い断定的文の連なりにすぎない。

The song, in fact, is more a loose improvisation, a stream-of-consciousness monologue let loose over a repetitive guitar groove. This groove, or what Hooker called his ‘boogie’, proved to be so irresistible that it eventually formed the basis of more than one third of his early recorded output. Why did the boogie hold such appeal for audiences, who purchased the recordings of ‘Boogie Chillen’ and its many knock-offs and imitations?

実際のところ、この曲は厳密に構成された作品というよりも、反復されるギター・グルーヴの上に解き放たれた、意識の流れ的な独白に近い、緩やかな即興演奏である。このグルーヴ、すなわちフッカー自身が「ブギ」と呼んだものは、あまりにも抗いがたい魅力を備えていたため、やがて彼の初期録音作品の3分の1以上の基盤を成すことになった。ではなぜ、このブギは、『Boogie Chillen』やその数多くの焼き直し、模倣作を購入した聴衆にとって、これほどまでに強い訴求力を持っていたのだろうか。

Blues historians have described Hooker’s boogie as a ‘rhythmic drone, twisting and turning the sound’ (Oakley 1997, p. 220), a ‘jumping, polyrhythmic groove’ (Murray 2002, p. 127) that can ‘rattle your bones’ (Davis 1995, p. 218). Equally colourful is the rhetoric of popular magazine writers. According to Downbeat magazine’s obituary, Hooker’s boogie had a ‘soulful, grinding edge. Once Hooker locked into a boogie . . . the most powerful hurricane could not knock him out of his groove’ (Koransky 2001, p. 16). To sound like him, advises Guitar Magazine, try ‘dispersing with everything but the upbeats [to] get unadulterated, driving syncopation’ (Ellis 2005, p. 110). Hooker himself had difficulty in describing the origins of his boogie. ‘It’s just there. I can’t explain it. And it just comes out’ (O’Neal and van Singel 2002, p. 204).

ブルース研究者たちは、フッカーのブギを「音をねじ曲げ、うねらせるリズミックなドローン」(Oakley 1997, p.220)、「跳ね回るようなポリリズミック・グルーヴ」(Murray 2002, p.127)、さらには「骨身を揺さぶる」もの(Davis 1995, p.218)として描写してきた。同様に、一般誌の音楽ライターによる言説もきわめて生彩に富んでいる。たとえばDownbeat誌の追悼記事によれば、フッカーのブギには「魂を帯びた、きしむようなエッジ」があり、「ひとたびフッカーがブギにロックインすると……最も強力なハリケーンでさえ、彼をそのグルーヴから引き離すことはできなかった」(Koransky 2001, p.16)という。またGuitar Magazineは、フッカーのサウンドに近づくための助言として、「アップビート以外のすべてを捨て去り、純度の高い、推進力のあるシンコペーションを得よ」(Ellis 2005, p.110)と述べている。一方で、フッカー自身は、自らのブギの起源を言葉で説明することに困難を感じていた。「ただ、そこにあるんだ。説明できない。ただ、自然に出てくるだけさ」(O’Neal & van Singel 2002, p.204)。

When pressed, he would sometimes cite his step-father Will Moore, a guitarist who played in the Clarksdale, Mississippi area before World War II, as the originator of this distinctive boogie rhythm. But Moore is a puzzling figure who does not figure in any of the oral histories related to the Delta blues, making it difficult to trace specific linkages between Hooker’s own style of playing and the Delta tradition.

問い詰められると、フッカーはときおり、第二次世界大戦以前にミシシッピ州クラークスデール周辺で演奏していたギタリストである義父ウィル・ムーアを、この独特なブギ・リズムの源として挙げることがあった。しかしムーアは謎の多い人物であり、デルタ・ブルースに関する口承史のいずれにも登場しない。そのため、フッカー自身の演奏様式とデルタ・ブルースの伝統とのあいだに、具体的な系譜的連関をたどることは困難である。

Although the early history of Hooker’s sound may elude us, this paper hopes to unravel some of his boogie’s visceral and hypnotic aspects by focusing on its rhythmic properties. The blues literature has allocated limited space to the subject of rhythm, but a salient feature that has received some attention is the irregularity of metre and hypermetre in the music of bluesmen Blind Lemon Jefferson (Evans 2000) and Robert Johnson (Ford 1998). Titon’s (1994, pp. 144–52) insightful rhythmic analyses of ‘downhome’ blues cover some of the topics addressed in this paper, including tempo fluctuation and the interplay of duple and triple rhythms.

フッカーのサウンドの初期史は、いまだ十分に解明されていない部分が多いが、本稿は、そのリズム的特性に焦点を当てることで、彼のブギが持つ身体的(ヴィセラル)かつ催眠的な側面のいくつかを解きほぐすことを目的とする。ブルース研究において、リズムという主題に割かれてきた紙幅は決して多くないが、一定の注目を集めてきた顕著な特徴として、ブラインド・レモン・ジェファーソン(Evans 2000)やロバート・ジョンソン(Ford 1998)の音楽に見られる、拍子およびハイパーメトルの不規則性が挙げられる。また、ティトン(1994, pp.144–152)による「ダウンホーム・ブルース」の鋭いリズム分析は、本稿で扱う論点のいくつか――テンポの揺らぎや、二拍系と三拍系リズムの相互作用など――をすでに包含している。

This last topic is central to Stewart (2000), who lays out the rhythmic transformation of popular music in America as a transition from shuffle (‘swing’) to duple (‘even’) rhythms. Our aim here will be to focus on only a fraction of the rhythmic components that make up Hooker’s boogie, all the while recognising that his boogie is greater than the sum of its parts. We shall undoubtedly overlook important elements, unintentionally in unforeseen ways which we hope other writers will address, and intentionally in several ways, one of which requires mention. Our analysis is restricted to the first four years of Hooker’s recorded output (Detroit 1948 to 1951), mainly because this period finds his boogie in its most original and bare form.

この最後の論点は、アメリカのポピュラー音楽におけるリズム変容を、シャッフル(「スウィング」)から二拍系(「イーヴン」)への移行として整理した Stewart(2000)の議論において中心的な位置を占めている。本稿の目的は、フッカーのブギを構成するリズム要素のごく一部に焦点を当てることにあるが、同時に、彼のブギが単なる要素の総和を超えた存在であることも認識しておく。

その結果として、本稿では重要な要素を見落とすことが避けられないだろう。それらの見落としは、ある場合には意図せず、予期せぬ形で生じるだろうし、それについては他の研究者が補ってくれることを期待したい。また、いくつかの点については意図的に扱わないが、そのうち一つについては言及しておく必要がある。

本分析は、フッカーの録音キャリアの最初の4年間(1948年のデトロイト録音から1951年まで)に限定されている。主な理由は、この時期において彼のブギが最も独創的で、最も削ぎ落とされた形で示されているからである。

Two tempo regions

二つのテンポ領域

Prior to delving into the boogie’s rhythmic detail, it will be helpful to gain a bird’s eye view of Hooker’s overall rhythmic landscape by examining his choice of song tempos. These span a wide spectrum of metronome markings ranging roughly from 60 to 220 beats per minute – a testament to the blues’ ‘enormous potential for tempo transformation’ (Kubik 1999, p. 86).

ブギのリズム的細部に踏み込む前に、フッカーが選択した楽曲テンポを検討することで、彼のリズム世界全体を俯瞰しておくことが有益である。それらは、およそ60〜220拍/分(bpm)に及ぶ幅広いメトロノーム値に分布しており、これはブルースがもつ「テンポ変容における驚異的な潜在力」(Kubik 1999, p.86)を裏づけるものである。

In the middle of this range, however, there is a narrow strip of unused tempo markings: of the 180-plus songs that Hooker recorded between 1948 and 1951, none is faster than 110 and slower than 130 beats per minute. In other words, there is a gap between these two metronome values that provides a clear-cut separation between the slow and up-tempo songs.

しかし、この範囲の中間には、ほとんど使用されていない狭いテンポ帯が存在する。1948年から1951年にかけてフッカーが録音した180曲以上の作品のうち、110 bpmより速く、かつ130 bpmより遅いテンポの楽曲は一曲も存在しない。言い換えれば、この二つのメトロノーム値のあいだには明確な空白があり、それがスロー・テンポ曲とアップ・テンポ曲をはっきりと分断している。

This divide allows us to categorise Hooker’s early oeuvre according to two tempo regions, which we will call blues (60–110 bpm) and boogie (130–220 bpm). The sizeable buffer zone between the two regions underscores their stylistic differences.

この分断により、フッカーの初期作品群は、二つのテンポ領域に分類することが可能となる。本稿ではそれらを、ブルース(60〜110 bpm)とブギ(130〜220 bpm)と呼ぶことにする。両領域のあいだに存在する相当な緩衝帯は、両者の様式的差異を強く示唆している。

A blues may be as fast as 110 bpm; speed it up further and its inherent rhythmic makeup becomes – to Hooker’s ears, we must presume – unacceptably agitated. Likewise, a boogie begins to sound languid once it dips below 130 bpm, the tempo of Hooker’s slowest unaccompanied boogie, ‘Talkin’ Boogie’. (This hypothesis can be tested by artificially slowing the song’s tempo to 120 bpm with a time-expansion algorithm that retains the original pitch level, an operation that disintegrates the boogie’s rhythmic feel.)

ブルースは最大で110 bpmまで速くなりうるが、それ以上にテンポを上げると、その内在的なリズム構造は――フッカーの感覚においては、と推測されるが――過度にせわしないものになってしまう。同様に、ブギは130 bpmを下回ると、弛緩した印象を帯び始める。130 bpmという値は、フッカーが無伴奏で演奏した最も遅いブギ曲『Talkin’ Boogie』のテンポに相当する。(この仮説は、音高を保持したままタイム・エクスパンション・アルゴリズムを用いて楽曲テンポを人工的に120 bpmまで落とすことで検証できるが、その操作によってブギ特有のリズム感は崩壊してしまう。)

That Hooker’s boogie should comprise the fast-tempo category is obvious but not trivial. Fast tempos are generally associated with two characteristics not readily attributable to the slower-paced blues: dancing and physical restlessness – which may explain why younger people prefer fast tempos (LeBlanc et al. 1988) and why, in a 1968 Downbeat interview, Hooker explained that his ‘jump’ style was intended ‘for the kids’ (quoted in Evans 1982, p. 84).

フッカーのブギが高速テンポのカテゴリーに属することは明白であるが、決して自明なことではない。高速テンポは一般に、より遅いテンポのブルースには容易に帰属しがたい二つの特性――ダンス性と身体的な落ち着きのなさ――と結びついている。これは、若年層が高速テンポを好む理由(LeBlanc ほか 1988)や、1968年の DownBeat 誌のインタビューにおいて、フッカー自身が自らの「ジャンプ」・スタイルは「子どもたちのためのもの」だと説明していること(Evans 1982, p.84)を説明する要因かもしれない。

Besides raw speed, a distinguishing feature between the blues and boogie tempos relates to the ‘free’ speech-like rhythms. In Hooker’s blues, these brief passages usually consist of a unison (almost heterophonic) melody line shared by the guitar and voice, during which the otherwise unambiguous beat often evaporates momentarily. This rhythmic device occurs only within the blues tempo region (although not in every song).

純粋な速さに加えて、ブルースとブギのテンポを分けるもう一つの顕著な特徴は、「自由な」話し言葉的リズムの扱いに関係している。フッカーのブルースでは、こうした短いパッセージは通常、ギターと声が旋律線を共有するユニゾン(ほとんどヘテロフォニック)として現れ、その間、それまで明確であった拍感が一時的に消失する。このリズム手法は、(すべての曲に見られるわけではないが)ブルースのテンポ領域においてのみ現れる。

Of course, it makes sense that these free rhythms should be absent from the boogie, since their unpredictability would jar the groove- and dance-inducing regularity of up-tempo music. Even though the spoken and sung passages in boogies do exhibit considerable rhythmic freedom, they float above a steady pulse without impinging upon it.

言うまでもなく、こうした自由リズムがブギに存在しないのは理にかなっている。その予測不可能性は、アップテンポ音楽に不可欠なグルーヴとダンスを誘発する規則性を損なってしまうからである。ブギにおける語りや歌唱のパッセージが相当なリズム的自由度を示すことは確かだが、それらは一定のパルスの上に浮遊する形をとり、その基盤を侵食することはない。

Duplets, triplets, and the mutable isoriff

デュプレット、トリプレット、そして可変的なイソリフ

With the exception of the free rhythms mentioned above, the principal organising force in Hooker’s blues and boogies is the triple subdivision of the beat, sometimes completely filled in and sometimes with a tacit middle subdivision that produces a long-short rhythm. 12/8 is generally recognised as the de facto metre of blues music, although many exceptions can be cited.

前述した自由リズムの例外を除けば、フッカーのブルースおよびブギにおける主要な組織原理は、拍の三分割である。それは、三つすべてが完全に埋められる場合もあれば、中間の分割が暗黙のまま省略され、ロング–ショート型のリズムを生み出す場合もある。12/8拍子は一般にブルース音楽の事実上の拍子として認識されているが、例外は数多く挙げることができる。

For instance, Charley Patton’s first country blues recordings from 1929 omit the triplet entirely (Stewart 2000); 12/8 metre does not figure prominently until his final recordings in 1934.

たとえば、チャーリー・パットンの1929年の最初期カントリー・ブルース録音では、トリプレットが完全に省略されている(Stewart 2000)。12/8拍子が彼の音楽に顕著に現れるのは、1934年の最終録音期になってからである。

Blind Lemon Jefferson’s introduction to his (1927) ‘Matchbox Blues’ makes explicit use of even quavers; the mostly-triplet feel that ensues in the accompaniment is frequently warped into moments of duple subdivisions.

ブラインド・レモン・ジェファーソンによる1927年の『Matchbox Blues』のイントロダクションでは、イーヴンな八分音符が明確に用いられている。その後に続く伴奏はおおむねトリプレット的な感触をもつものの、しばしば二分割的な瞬間へと歪められる。

Robert Johnson’s (1936) ‘Cross Road Blues’ also shifts back and forth between two’s and three’s, although the governing metre is clearly compound (as in all his other slow blues from that decade).

ロバート・ジョンソンの1936年の『Cross Road Blues』も、二分割と三分割のあいだを行き来するが、その支配的拍子は明らかに複合拍子である(同時期の彼の他のスロー・ブルースと同様である)。

Sometimes, Johnson’s rhythm undergoes a gradual microrhythmic morphing from triplet to duplet and back, as in the alternate take of ‘Ramblin’ On My Mind’ (Benadon 2007).

場合によっては、ロバート・ジョンソンのリズムが、トリプレットからデュプレットへ、そして再び戻るという、段階的なミクロリズム的変形を被ることもある。『Ramblin’ On My Mind』の別テイクがその例である(Benadon 2007)。

And the first-ever recorded vocal blues, Mamie Smith’s (1920) ‘Crazy Blues’, inhabits the metrically liquid zone of duple-triple ambiguity typical of jazz.

さらに、史上初の録音ヴォーカル・ブルースであるマミー・スミスの1920年の『Crazy Blues』は、ジャズに典型的な、二分割と三分割の曖昧さをもつ拍的に流動的な領域に位置している。

Thus, we are reminded that within the (nominally) duple/triple divide, there exists a rich amalgam of beat subdivisions.

このように見てくると、(名目上の)二分/三分という区分の内部には、きわめて豊かな拍分割の混合体が存在していることが改めて確認される。

We also find exceptions to ternary subdivision in Hooker’s music. Within the blues tempo region, these are microrhythmically derived rather than metrical, as in Robert Johnson’s example above. In other words, Hooker sometimes tones down the 2-to-1 ratio of the ternary long-short pattern by evening out the durations of the two notes, a feature of jazz rhythm (Friberg and Sundström 2002; Benadon 2006) and possibly of rhythm production in general (Collier and Wright 1995).

また、フッカーの音楽には、三分割拍分割からの例外も見いだされる。ブルースのテンポ領域において、これらは拍子的なものというよりもミクロリズム的に生成されており、先に挙げたロバート・ジョンソンの例と同様である。言い換えれば、フッカーはときに、三分割に基づくロング–ショート・パターンの2対1という比率を弱め、二つの音の持続時間をより均等化する。この特徴は、ジャズ・リズムの性質として知られているだけでなく(Friberg & Sundström 2002;Benadon 2006)、リズム生成一般に見られる可能性も指摘されている(Collier & Wright 1995)。

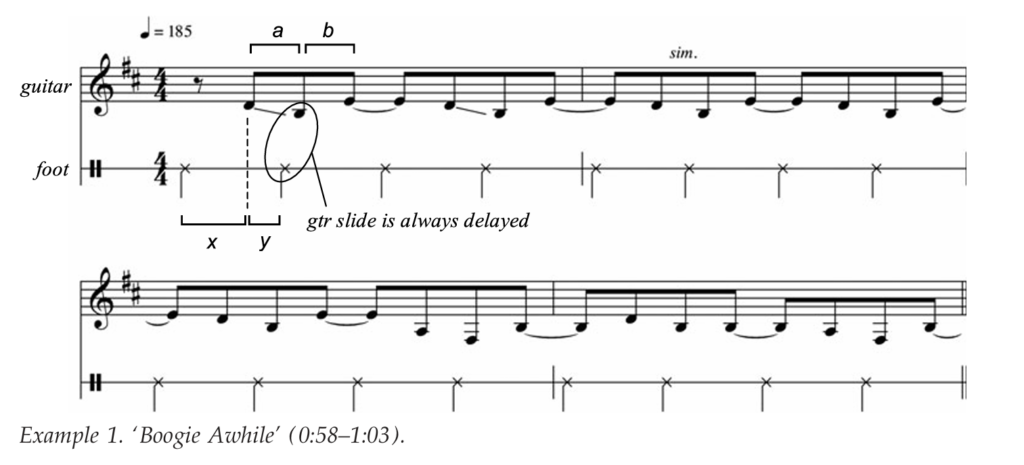

The boogie also exhibits the expected microrhythmic variance typical of long-short pairs. For instance, in ‘Boogie Awhile’ (Example 1), scarcely any beats break down cleanly into a triplet – the long-short ratio being frequently skewed in favour of the second note in the pair – so much so, that at times the durations are unambiguously even.

ブギにもまた、ロング–ショート型の音対に典型的な、予期されるミクロリズム的変動が見られる。たとえば『Boogie Awhile』(例1)では、拍がきれいにトリプレットへ分解されることはほとんどなく、ロング–ショート比はしばしば音対の第二音の側に歪められる。その結果、場合によっては二つの音の持続時間が明確に等しいと感じられるほどである。

More significantly, Hooker challenges many assumptions about musical logic by producing a rhythm that sounds long-short no matter how it is approached – upbeats to beats or vice versa. Normally, if a rhythm’s beat/upbeat pattern is long-short, then its upbeat/beat pattern should be the reverse, short-long. But not here.

さらに重要なのは、フッカーが、音楽的論理に関する多くの前提を揺さぶるようなリズムを生み出している点である。すなわち、このリズムは、アップビートからビートへと聴いても、ビートからアップビートへと聴いても、常にロング–ショートとして知覚される。通常であれば、あるリズムのビート/アップビート関係がロング–ショートであれば、その逆であるアップビート/ビート関係はショート–ロングになるはずだ。しかし、ここではそうならない。

The duration ratios for Example 1 are shown in Table 1. Values near 2.0 represent a ternary long-short 2-to-1 ratio between two adjacent notes, values near 1.0 represent an even 1-to-1 ratio (two equidurational quavers), and intermediate values (such as 1.5) denote evened-out long-short patterns.

例1の持続時間比は表1に示されている。2.0付近の値は、隣接する二音のあいだに三分割的なロング–ショート(2対1)の比率が存在することを示し、1.0付近の値は等しい1対1の比率(等時的な二つの八分音符)を表す。また、1.5のような中間値は、均等化されたロング–ショート・パターンを示している。

Two concurrent relationships are at play: beat/upbeat (x:y) and upbeat/beat (a:b) pairs. The foot acts as a metronome that provides the beats; they are subdivided by the guitar’s upbeats.

ここでは二つの関係が同時に作用している。すなわち、ビート/アップビート(x:y)と、アップビート/ビート(a:b)の音対である。足踏みはメトロノームのように機能してビートを提供し、それらがギターのアップビートによって下位分割される。

These x:y ratios are usually tripleted (shown in bold type), but enough of them are not to preclude a tidy triplet feel from forming.

これらの x:y 比は通常トリプレット的であり(太字で示されている)、すべてがそうでないにしても、整ったトリプレット感の形成を妨げるほどではない。

Still, the overall feel produced by foot beats and guitar upbeats is long-short (x greater than y), as expected in compound time.

それでも、足によるビートとギターのアップビートが生み出す全体的な感触は、複合拍子に典型的なロング–ショート(x が y より大)となっている。

But the guitar line in isolation reveals a puzzling piece of evidence.

しかし、ギターのラインだけを単独で見ると、不可解な証拠が浮かび上がる。

The a:b ratio measures the guitar’s upbeats (a) against its – rather than the foot’s – beat attacks (b).

a:b 比は、足ではなくギター自身のビート上のアタック(b)に対する、ギターのアップビート(a)を測定したものである。

To agree with the long-short x:y ratio, the a:b ratio should be short-long and therefore less than 1.0 (a short upbeat followed by a longer duration on the beat). In other words, the value of a should be smaller than the value of b.

ロング–ショートである x:y 比と整合するためには、a:b 比はショート–ロング、すなわち 1.0 未満であるはずである(短いアップビートの後に、より長いビート音が続く)。言い換えれば、a の値は b より小さくなるはずである。

However, in this case the guitar follows the opposite route: a is almost always longer than b, yielding a:b ratio values above 1.0.

しかしこの場合、ギターは正反対の振る舞いを示す。a はほぼ常に b よりも長く、その結果、a:b 比は 1.0 を上回る値を取る。

This occurs because the downward guitar slides lead to constant delays with respect to the foot. The result is a kaleidoscopic rhythm consisting predominantly of long-short patterns regardless of whether one listens to pairs of beats/upbeats (x:y) or upbeats/beats (a:b).

これは、ギターの下方スライドが足踏みに対して常に時間的な遅れを生じさせているために起こる。その結果として、ビート/アップビート(x:y)の音対として聴こうが、アップビート/ビート(a:b)の音対として聴こうが、いずれの場合にもロング–ショート・パターンが優勢となる、万華鏡的なリズムが生み出される。

Beyond microrhythm, duple subdivision often plays a central and explicit role, as with the transformed version of the motive shown in Example 2(a). Commonly referred to as the Elmore James riff (because he featured it on ‘Dust My Broom’ in 1951), this motive was in fact used rather extensively more than a decade earlier by Robert Johnson.

ミクロリズムを超えた次元では、二分割の拍分割がしばしば中心的かつ明示的な役割を果たす。その例が、例2(a)に示されたモティーフの変形である。一般にはエルモア・ジェイムズ・リフとして知られている(彼が1951年の『Dust My Broom』で用いたため)が、このモティーフ自体は、実際にはそれより10年以上前からロバート・ジョンソンによってかなり広範に使用されていた。

This riff, which we will refer to as the isoriff because it is isochronous and ‘isophonic’ (a single note or chord comprised of pitches from the tonic triad or tonic dominant), appears in almost all of Hooker’s Detroit recordings.

このリフは、本稿では等時的(isochronous)かつ「等音的(isophonic)」であることからイソリフ(isoriff)と呼ぶことにする。すなわち、主和音または主–属和音に含まれる音高から成る単音、あるいは和音で構成されている。このイソリフは、フッカーのデトロイト期の録音のほぼすべてに登場する。

Even though the isoriff is inherently a triplet, Hooker’s boogie often converts it into a duple construct, as shown in Example 2(b).

イソリフは本来的にはトリプレット構造をもつが、フッカーのブギでは、例2(b)に示されるように、それがしばしば二分割的構造へと変換される。

The reason for this might be purely practical, since maintaining the speed of the triplet at a boogie tempo may have translated into a technical feat beyond Hooker’s reach.

その理由は、純粋に実践的なものであった可能性がある。すなわち、ブギのテンポにおいてトリプレットの速度を維持することは、フッカーの技術的能力を超える難事であったのかもしれない。

Instead of abandoning the isoriff during the fast songs, Hooker essentially retains the motive’s basic physical speed, allowing it to fit comfortably into a binary rather than ternary subdivision of the beat.

しかしフッカーは、高速楽曲においてイソリフそのものを放棄するのではなく、モティーフの基本的な身体的スピードを保ったまま、それを拍の三分割ではなく二分割に無理なく収めている。

In a sense, the slower note value compensates for the faster tempo.

ある意味では、遅い音価が速いテンポを補償していると言える。

As mentioned previously, the spontaneous alternation of two- and three-way beat subdivisions is hardly exclusive to Hooker’s boogie.

先に述べたように、拍の二分割と三分割を即興的に行き来すること自体は、フッカーのブギに固有の現象ではない。

But the importance of his duple isoriff should not be understated, for it lies at the heart of what Stewart (2000, p. 296) calls a ‘sweeping metric shift in popular music that began in the 1950s’.

しかし、彼の二分割イソリフの重要性は過小評価されるべきではない。それは、Stewart(2000, p.296)が「1950年代に始まった、ポピュラー音楽における包括的な拍子転換」と呼ぶ現象の核心に位置しているからである。

He notes that as the decades passed, ‘the underlying rhythms of American popular music underwent a basic, yet generally unacknowledged transition from triplet or shuffle feel (12/8) to even or straight eighth notes (8/8)’ (ibid., p. 293).

Stewart は、時代が進むにつれて「アメリカのポピュラー音楽の基底リズムは、トリプレットあるいはシャッフル感(12/8)から、イーヴンまたはストレートな八分音符(8/8)へと、根本的ではあるが一般にはほとんど意識されない転換を遂げた」と指摘している(同書, p.293)。

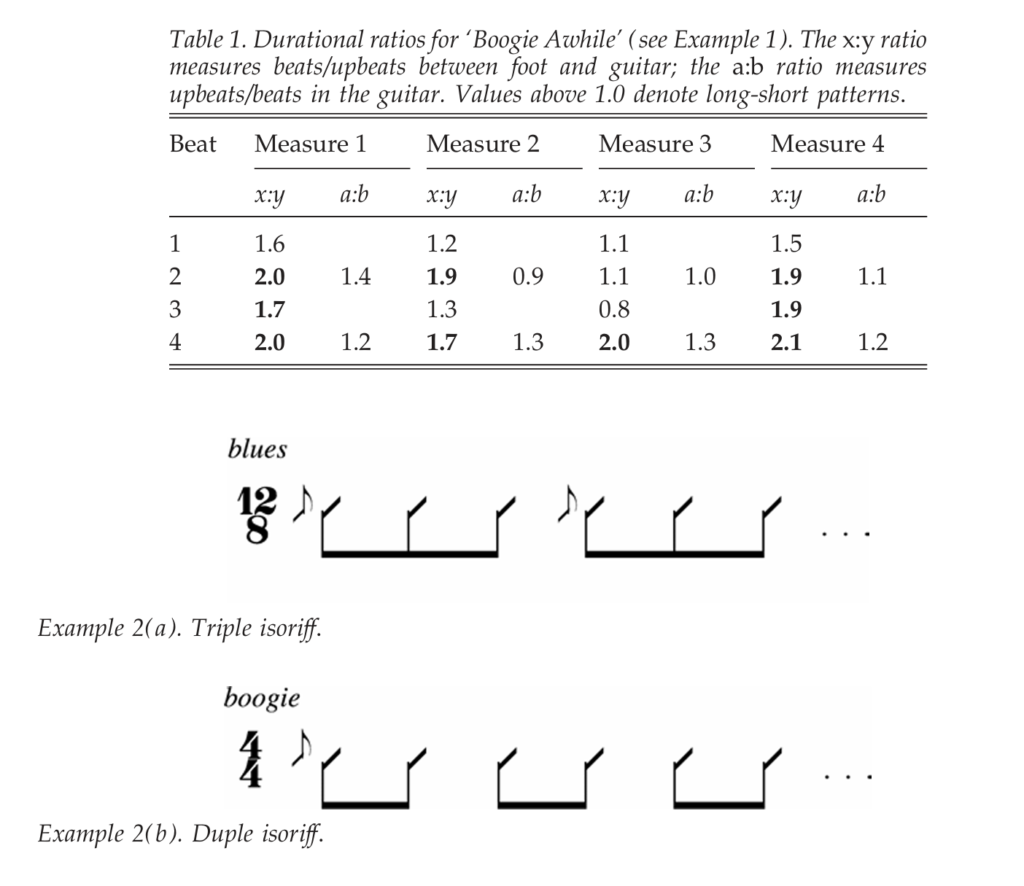

Figure 1 illustrates the changing note values that comprise the isoriff as it migrates across tempos. Notice how the isoriff operates within well-defined temporal boundaries. Its notes are about 300 milliseconds at their slowest and 150 ms at their fastest – regardless of their actual music notation values. No boogie contains triplet-quaver isoriffs because they would be too fast (less than 150 ms per note).

図1は、テンポの変化に伴ってイソリフを構成する音価がどのように変化するかを示している。ここで注目すべきは、イソリフが明確に定義された時間的境界の内部で機能している点である。イソリフの各音の持続時間は、最も遅い場合で約300ミリ秒、最も速い場合で約150ミリ秒であり、実際の楽譜上の音価が何であれ、この範囲を外れることはない。ブギにおいて三連八分音符のイソリフが存在しないのは、その速度が速すぎ(1音あたり150ミリ秒未満)て成立しないからである。

Conversely, quaver isoriffs are too slow (more than 300 ms) for the blues and are therefore absent from that tempo region.

逆に、八分音符のイソリフはブルースにとっては遅すぎ(300ミリ秒超)るため、そのテンポ領域には現れない。

Hence, the isoriff can take on either form provided it lies within the rather narrow temporal band of 150–300 ms.

したがって、イソリフは、150〜300ミリ秒という比較的狭い時間帯に収まる限りにおいて、いずれの形態も取りうることになる。

It is interesting to note how the quaver (○ in the graph) dovetails roughly where the trendline of the triplet-quaver (●) trails off, providing a link across the blues/boogie tempo gap mentioned earlier.

興味深いのは、グラフ中の八分音符(○)が、三連八分音符(●)のトレンドラインが消えゆく地点とほぼ重なり合うように接続しており、先に述べたブルース/ブギ間のテンポの空白を橋渡ししている点である。

The graph also shows that at sufficiently fast tempos, the isoriff can take the form of crotchet triplets (d), or even crotchets (×) if the tempo is faster still.

さらにこのグラフは、テンポが十分に速くなると、イソリフが四分音符の三連形(d)を取りうること、さらにはテンポがそれ以上に速い場合には、四分音符(×)として現れることも示している。

This metrical fluidity suggests that the isoriff’s character is defined more by the raw physicality of successive strokes than by the actual note values, which result from accommodating the riff’s technical demands to the given tempo. Thus, a 194 ms-per note isoriff can comprise quavers at 156 bpm (as in ‘Good Business’) or crotchet triplets at 206 bpm.

このような拍子的流動性は、イソリフの性格が、実際の音価そのものよりも、連続するストロークの生々しい身体性によって規定されていることを示唆している。実際の音価は、与えられたテンポに対してリフの技術的要求を適合させた結果として生じるにすぎない。したがって、1音あたり194ミリ秒のイソリフは、156 bpm では八分音符(『Good Business』の場合)として、206 bpm では四分音符三連形として構成されうる。

It is also common for more than one type of isoriff to appear within the same song, as in ‘My Baby’s Got Something’, ‘Talkin’ Boogie’, and ‘Goin’ Mad Blues’.

また、『My Baby’s Got Something』、『Talkin’ Boogie』、『Goin’ Mad Blues』のように、同一楽曲の中に複数のタイプのイソリフが現れることも一般的である。

At times, the boogie begins with a fanfare-like isoriff that is so metrically nondescript that the tempo remains a mystery until the isoriff subsides and the foot stomping joins in.

ときには、ブギがファンファーレのようなイソリフで始まり、その拍的性格があまりにも不定形であるため、イソリフが収束し、足踏みが加わるまでテンポが判然としないことがある。

For instance, the opening isoriff of ‘She Left Me By Myself’ can be heard as being made up of triplets (if this were a 92 bpm blues) or quavers (a ‘slow’ 140 bpm boogie); instead, the entrance of Hooker’s foot, which will tap at a rate of 184 times per minute, reveals the thumb downstrokes to have been crotchet triplets.

たとえば『She Left Me By Myself』の冒頭イソリフは、92 bpm のブルースであればトリプレットとして、あるいは「遅め」の140 bpm ブギであれば八分音符として聴くことができる。しかし、やがてフッカーの足踏みが1分間に184回の速度で加わることで、親指によるダウンストロークが四分音符三連形であったことが明らかになる。

A similar guessing game opens ‘Boogie Chillen 2 (Jump Chillen)’, where the isoriff accelerates as much as it disorients.

同様の推測を要する状況は『Boogie Chillen 2(Jump Chillen)』の冒頭にも見られ、そこではイソリフが加速すると同時に、聴き手の方向感覚を強く攪乱する。

In ‘Boogie Chillen 2 (I Gotta Be Comin’ Baby)’, the metric relationship between foot stomp and isoriff is so tenuous – likely a result of Hooker changing his mind as to the song’s appropriate tempo – that one must wait another minute-and-a-half for the return of the isoriff to confirm the crotchet triplet guess as correct.

さらに『Boogie Chillen 2(I Gotta Be Comin’ Baby)』では、足踏みとイソリフの拍的関係がきわめて希薄であり――おそらくフッカーが曲にふさわしいテンポについて途中で考えを変えた結果だと思われるが――四分音符三連形という仮説が正しいことを確認するには、イソリフが再び現れるまでさらに1分半ほど待つ必要がある。

The isoriff, then, is a metrically malleable figure par excellence (London 2004).

以上のことから、イソリフはまさに拍子的可塑性を体現する典型的な図形であると言える(London 2004)。

Metric malleability occurs with melodic or rhythmic figures that can be interpreted in more than one metric context, although performers usually disambiguate these kinds of patterns with such cues as expressive timing and dynamics (London 2004, p. 79).

拍子的可塑性とは、旋律的あるいはリズム的な図形が複数の拍的文脈のもとで解釈可能な場合に生じる現象であり、通常は演奏者が表情的なタイミングや強弱といった手がかりによって、その曖昧さを解消する(London 2004, p.79)。

In the isoriff’s case, the disambiguating detail consists of a grace note-like slide or hammer-on that Hooker sometimes injects every three or six strokes if the isoriff is a triplet or every eight if it is a duplet.

イソリフの場合、その曖昧さを解消する要素は、フッカーがときおり挿入する装飾音的なスライドやハンマリング・オンである。これらは、イソリフがトリプレットである場合には3回または6回ごとに、デュプレットである場合には8回ごとに挿入されることがある。

Even though a detailed analysis of blues guitar technique is beyond the scope of this article, our discussion of the isoriff leads naturally to some brief observations about Hooker’s right-hand approach. There are several versions of the isoriff, ranging from single-string picking to multiple-string chord bashing. Two of the isoriff types employ the thumb only, either to pick a single-note rhythm in the low or middle register, or to brush full chords with thumb downstrokes. In another version of the isoriff, the thumb and index finger work together, providing the chord’s bass note and the index finger brushing two or three treble strings upstroke to complete the chord. Sometimes the thumb rests, leaving only the index or middle finger to brush upstroke dyads or triads in the treble register.

ブルース・ギター技法の詳細な分析は本稿の射程を超えるが、イソリフに関する議論は、フッカーの右手奏法についていくつかの簡潔な観察を自然に導く。イソリフには、単弦のピッキングから複数弦を叩きつけるようなコード奏法に至るまで、いくつかのヴァリエーションが存在する。イソリフのうち二つのタイプでは親指のみが用いられ、低音域または中音域で単音リズムを弾く場合と、親指のダウンストロークでフル・コードをかき鳴らす場合がある。別のタイプのイソリフでは、親指と人差し指が協働し、親指がコードのベース音を担い、人差し指がアップストロークで高音弦を2〜3本ブラッシングしてコードを完成させる。場合によっては親指が休み、人差し指または中指のみが高音域でアップストロークの二和音や三和音をブラッシングすることもある。

According to Cohen’s (1996) classification of blues picking styles and hand postures, Hooker’s mixed approach to timekeeping places him in the ‘utility-thumb’ category, in contrast to the ‘dead-thumb’ and ‘alternating-thumb’ players, who confined the thumb to basic beat-keeping either on a single bass string or alternating between two low strings. More specifically, Cohen sees Hooker’s boogie as a hybrid of utility- and dead-thumb approaches, ‘a younger style’ of the post-War era (ibid., p. 472).

Cohen(1996)によるブルースのピッキング様式および手の構えの分類によれば、フッカーの混合的なタイムキーピングのアプローチは「ユーティリティ・サム」型に位置づけられる。これは、親指を単一の低音弦、あるいは二本の低音弦の交互打弦による基本的な拍取りに限定する「デッド・サム」型や「オルタネーティング・サム」型の奏者とは対照的である。さらに具体的には、Cohen はフッカーのブギを、ユーティリティ・サムとデッド・サムの折衷形、すなわち戦後期に現れた「より新しいスタイル」と捉えている(同書, p.472)。

Hearing double

二重に聴くこと

The underlying rhythmic engine of Hooker’s boogie is the perpetual cycle of alternating long beats and short upbeats. This pattern appears in many composite guises that include strumming, foot taps, muffled strings, picked monophonic lines, staccato chords, and even ‘loud’ rests, a term devised by London (2004, p. 87) to describe unexpected silences on strong beats.

フッカーのブギを駆動する根底的なリズム機構は、ロングなビートとショートなアップビートが永続的に交替する循環である。このパターンは、ストローク、足踏み、ミュートされた弦、単音のピッキング・ライン、スタッカートの和音、さらには強拍上に生じる予期せぬ沈黙を指すロンドン(2004, p.87)の言う「ラウドな休符」に至るまで、さまざまな複合的形態として現れる。

Iyer (2002) believes that long-short patterns are conducive to stream segregation, the phenomenon whereby the mind separates the auditory stimulus into two or more ‘auditory objects’ (Bregman 1990).

Iyer(2002)は、ロング–ショート・パターンがストリーム分離を促進すると考えている。ストリーム分離とは、聴覚刺激が心的に二つ以上の「聴覚的対象」へと分離される現象である(Bregman 1990)。

Such rhythmic unevenness is also present in jazz, where the ‘swung’ eighth-note facilitates the perception of higher level rhythmic structure. An immediate consequence of the swing feel is that it suggests the next level of hierarchical organization. In conventional terms, the swung eighth-note pairs are perceptually grouped into the larger regular interval, that is, the quarter note. If all subdivisions were performed with exactly the same duration, it would be more difficult to perceive the main beat. The lengthening of the first of two swung notes in a pair amounts to a durational accentuation of the beat. . . . The observation that swing enhances the perception of the tactus is no surprise, given its primary function in dance contexts. (Iyer 2002, pp. 404–5)

このようなリズムの不均等性はジャズにも見られ、「スウィングされた」八分音符は、より高次のリズム構造の知覚を促進する。スウィング感がもたらす直接的な帰結は、次の階層的組織レベルを示唆する点にある。通常の理解では、スウィングされた八分音符の対は、より大きな規則的時間単位、すなわち四分音符として知覚的にまとまる。もしすべての下位分割が完全に同一の持続時間で演奏されたとすれば、主拍を知覚することはより困難になるだろう。スウィング対において最初の音が引き伸ばされることは、ビートに対する持続時間的な強調に相当する。……スウィングがタクトゥス(基本拍)の知覚を強化するという観察は、ダンス文脈におけるその主要な機能を考えれば、驚くにはあたらない(Iyer 2002, pp.404–405)。

In Hooker’s boogie, the syncopation generated by the omnipresent upbeats is so prominently featured that one is led to wonder whether they, and not the beats, carry the groove’s timekeeping function. Hence, the boogie can be seen as a dichotomous framework in which beats and upbeats vie for control of the listener’s internal clock via stream segregation.

フッカーのブギでは、遍在するアップビートによって生み出されるシンコペーションがあまりにも前景化されているため、グルーヴのタイムキーピング機能を担っているのはビートではなく、むしろアップビートなのではないかという疑念が生じる。したがって、ブギは、ストリーム分離を介して、ビートとアップビートが聴取者の内的時計の支配を争う二分的枠組みとして捉えることができる。

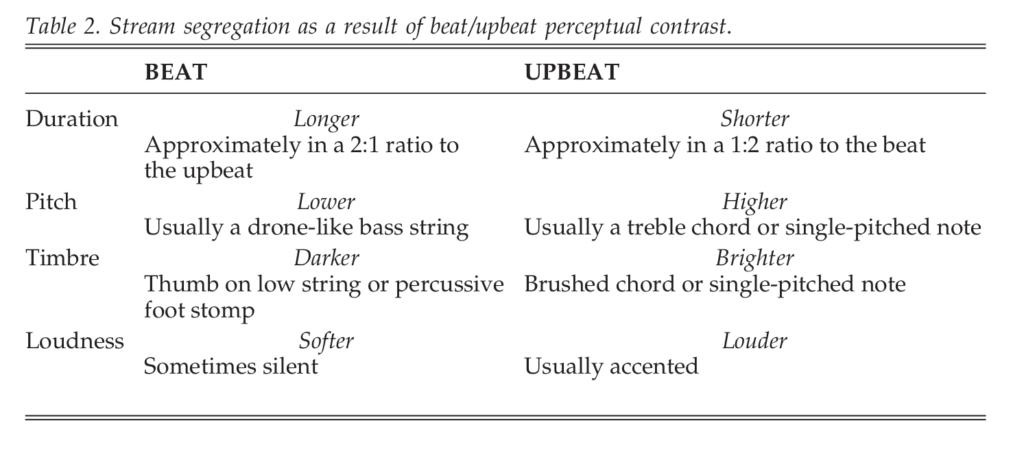

Moore and Gockel (2002) have suggested that stream segregation is dependent on the degree of perceptual difference between successive sounds. According to this paradigm, the more two adjacent sounds differ in duration, pitch height, timbre, and/or loudness, the more likely it will be for the sounds to segregate. Such is usually the case in Hooker’s boogie, whose beat/upbeat cycle features all of the above-mentioned perceptual differences. Added together, this creates the ear-boggling illusion of two parallel, quasi-simultaneous pulse keepers (Table 2).

Moore と Gockel(2002)は、ストリーム分離が連続する音同士の知覚的差異の度合いに依存すると示唆している。この枠組みによれば、隣接する二音が、持続時間、音高、音色、そして/あるいは音量においてより大きく異なるほど、それらの音は分離して知覚されやすくなる。フッカーのブギにおけるビート/アップビートの循環は、通常、これらすべての知覚的差異を備えている。これらが重なり合うことで、二つの並行的で、ほぼ同時に存在するパルス保持者があるかのような、耳を惑わせる錯覚が生み出されるのである(表2)。

Moreover, Bregman and Campbell (1971) have shown that listeners can have a difficult time determining the order of tones within a fast repeated cycle of highs and lows. This is because a further consequence of stream segregation is that it hinders temporal order judgements, especially given a close temporal proximity between events – as in the boogie’s upbeats and beats (see Moore 2003, pp. 288–9 for a review).

さらに、Bregman と Campbell(1971)は、高音と低音が高速で反復される循環の中では、聴取者が音の順序を判断することが困難になりうることを示している。これは、ストリーム分離のさらなる帰結として、時間的順序判断が阻害されるためであり、とりわけ、ブギにおけるアップビートとビートのように、出来事同士が時間的にきわめて近接している場合に顕著である(概説については Moore 2003, pp.288–289 を参照)。

Consider what happens to the long-short pattern as the tempo is increased, say from a slow blues to a fast boogie: the temporal interval between the upbeat (short note) and the subsequent downbeat (long) decreases. In theory, we could increase the tempo as much as we please to bring the upbeat closer and closer to the downbeat. At a sufficiently fast tempo, the two notes’ extreme proximity renders their temporal ordering ambiguous – that is, the listener becomes unsure of which of the two notes is played first and which second.

テンポが、たとえばスローなブルースから高速なブギへと引き上げられたとき、ロング–ショート・パターンに何が起こるかを考えてみよう。アップビート(短い音)と、それに続くダウンビート(長い音)との時間間隔は縮小する。理論上は、テンポをいくらでも上げることで、アップビートをダウンビートへと限りなく近づけることができる。十分に速いテンポにおいては、二音の極端な近接性によって、その時間的順序が曖昧になり、すなわち、どちらの音が先に演奏され、どちらが後なのかを聴取者が判断できなくなる。

This ‘temporal order threshold’ has been determined to be as large as 200 ms (Warren et al. 1969) and as little as 50 ms (Winckel 1967), depending on how the experiment is constructed.

この「時間順序の閾値」は、実験の構成方法によって、最大で200ミリ秒(Warren ほか 1969)、最小で50ミリ秒(Winckel 1967)と報告されている。

Within the range of boogie tempos, the duration of the upbeat triplet-quaver ranges from 100 to 142 ms, which suggests that at least some temporal ambiguity is likely to arise.

ブギのテンポ範囲において、アップビートの三連八分音符の持続時間は100〜142ミリ秒の間に分布しており、少なくともある程度の時間的曖昧さが生じる可能性が高いことを示唆している。

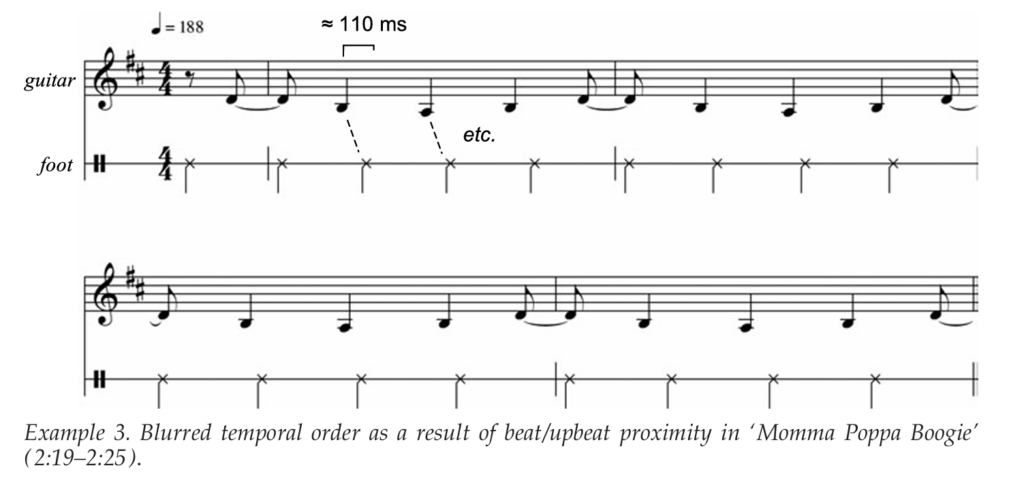

Examples of this beat/upbeat diffusion abound in Hooker’s boogies, as in ‘Momma Poppa Boogie’ (Example 3).

このようなビート/アップビートの拡散現象は、フッカーのブギに数多く見られ、『Momma Poppa Boogie』(例3)もその一例である。

Like a dog chasing its own tail, the upbeat guitar note precedes Hooker’s foot taps by such a narrow margin (about one tenth of a second) that one is dizzied by the blur of their cyclical alternation. Indeed, at times it appears as if the foot is providing the upbeats and the guitar the downbeats.

まるで自分の尻尾を追いかける犬のように、アップビートのギター音はフッカーの足踏みよりもごくわずか(約10分の1秒)だけ先行し、その循環的な交替の曖昧さによって、聴き手は目眩を覚えるほどである。実際、ときには足がアップビートを、ギターがダウンビートを提供しているかのようにさえ感じられる。

A potent mix

強力な混合

Although other blues guitarists employed boogie rhythms, they typically imitated the stylistic devices of piano players. This was a popular recipe with blues fans. During a seven-year period, for example, Jimmy Reed enjoyed no fewer than eighteen hits that reached the Billboard R&B charts, building most of these performances off simple piano-type boogie riffs translated to the guitar. Other blues artists – Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Elmore James – may have earned more respect from serious blues fans and music writers, but none of them could match Reed’s sheer popularity in the late 1950s. Many garage bands and aspiring blues guitarists imitated Reed’s performances, which employed simple figures, easy to learn and play.

他のブルース・ギタリストたちもブギのリズムを用いてはいたが、彼らは典型的にピアノ奏者の様式的手法を模倣していた。これはブルース・ファンのあいだで広く受け入れられていた定番の方法である。たとえばジミー・リードは、7年間のあいだに少なくとも18曲を Billboard の R&B チャートに送り込み、その多くを、ピアノ型の単純なブギ・リフをギターに移し替えた演奏によって築き上げた。マディ・ウォーターズ、ハウリン・ウルフ、エルモア・ジェイムズといった他のブルース・アーティストたちは、熱心なブルース・ファンや音楽評論家からはより高い評価を得ていたかもしれないが、1950年代後半におけるリードの圧倒的な人気に匹敵する者はいなかった。多くのガレージ・バンドや志望するブルース・ギタリストたちは、学びやすく演奏しやすい単純な音型を用いたリードの演奏を模倣したのである。

Hooker’s boogie rhythms were also popular but, in contrast to Reed’s, proved far more difficult to imitate. He had transformed the boogie from a simple jam session beat to a taut system of feints and counter-feints that not only played the beat, but played with it as well.

フッカーのブギ・リズムもまた人気を博したが、リードのそれとは対照的に、はるかに模倣が困難であった。彼はブギを、単純なジャム・セッション的ビートから、ビートを演奏するだけでなく、それと戯れることさえ含んだ、緊張感に満ちたフェイントと逆フェイントの体系へと変貌させたのである。

To be sure, the rhythmic features mentioned above – upbeat/downbeat proximity, up-tempo vamping, long-short rhythmic patterns – can be found in other musical styles during the decades leading to Hooker’s first recordings. But Hooker’s (or Will Moore’s) contribution lay in the innovative rhythmic concoction of these elements.

確かに、これまでに挙げてきたリズム的特徴――アップビートとダウンビートの近接、アップテンポのヴァンピング、ロング–ショート型のリズム・パターン――は、フッカーの最初期の録音に先立つ数十年間の他の音楽様式にも見いだすことができる。しかし、フッカー(あるいはウィル・ムーア)の貢献は、これらの要素を革新的に調合した点にあった。

More specifically, Hooker’s boogie conflated features from two dance-oriented black styles of music from the preceding decades: piano boogie-woogie and big band swing.

より具体的に言えば、フッカーのブギは、それ以前の数十年間における二つのダンス志向の黒人音楽様式――ピアノ・ブギウギとビッグバンド・スウィング――の特徴を融合させたものである。

Piano boogie-woogie is characterised by a relentless left-hand motto perpetuo within an up-tempo 12/8 feel. This two-measure cycle – sometimes referred to as ‘the sixteen’ because it contains that many quavers – constitutes the style’s principal driving force. As with Hooker’s boogie, the accented triplet upbeat is a recurring element.

ピアノ・ブギウギは、アップテンポの12/8感の中で、左手による執拗なモットー・ペルペトゥオ(反復音型)を特徴とする。この2小節の循環は、含まれる八分音符の数から「ザ・シックスティーン」と呼ばれることもあり、この様式の主要な推進力を成している。フッカーのブギと同様に、強調された三連のアップビートは反復的に現れる要素である。

But there is a crucial difference between the two styles. As discussed earlier, Hooker’s boogie tends to use upper-register (usually chordal) accents on the upbeat, providing a stark timbral contrast to the lower-register thumb notes and/or foot taps that mark the beat. Boogie-woogie lacks this perceptual differentiation.

しかし、この二つの様式のあいだには決定的な違いがある。先に述べたように、フッカーのブギは、アップビートにおいて高音域(通常は和音)のアクセントを用いる傾向があり、ビートを刻む低音域の親指音や足踏みと、きわめて鮮明な音色的対比を生み出す。ブギウギには、このような知覚的差異化が欠けている。

A style that is replete with accented triplet-upbeats is big band swing. But those upbeats which do form part of the essential driving force in the rhythm section, such as the ride cymbal or piano’s chordal comping, are not incessantly cyclical and therefore not an integral ingredient of the overall groove. And they are not loud enough, either. The truly salient upbeat accents belong to the brass and saxophone sections, which, though frequent, are even less systematically cyclical.

強調された三連アップビートに満ちている様式としては、ビッグバンド・スウィングが挙げられる。しかし、ライド・シンバルやピアノのコード・コンピングのように、リズム・セクションにおいて推進力の一部を担うアップビートは、絶え間なく循環するものではなく、そのため全体的グルーヴの不可欠な要素とはなっていない。加えて、それらは音量の点でも十分に目立つわけではない。真に際立ったアップビートのアクセントは、ブラスやサクソフォンのセクションに属しており、それらは頻繁に現れるとはいえ、体系的な循環性はさらに乏しい。

Hence, Hooker’s boogie can be said to combine the best of both worlds because its main rhythmic cell, the tripleted long-short module, employs the pronounced perceptual distinction of upbeats found in big band swing and the non-stop cyclicality of piano boogie-woogie. Moreover, the static, drone-like harmony of Hooker’s boogie acts as a foil to its rhythmic syncopation, a quality that is absent from the harmonic mobility of the other two styles.

したがって、フッカーのブギは、その主要なリズム細胞である三連のロング–ショート・モジュールにおいて、ビッグバンド・スウィングに見られる明確なアップビートの知覚的差異と、ピアノ・ブギウギの途切れない循環性という、双方の長所を併せ持っていると言える。さらに、フッカーのブギに特有の静的でドローン的な和声は、そのリズム的シンコペーションを際立たせる対照物として機能しており、この性質は、他の二つの様式がもつ和声的可動性には見られないものである。

When Hooker’s boogie came face to face with the piano boogie-woogie in ‘Do the Boogie’ (recorded in 1949 and originally unreleased), his electric guitar avoided the stylistic contradictions by relinquishing the leading role. This first accompanied boogie finds him mainly as vocalist and bandleader, with pianist James Watkin and drummer Curtis Foster carrying most of the rhythmic momentum. Later that year, Hooker let his groove mingle with that of his two accompanists in different versions of the instrumental ‘609 Boogie’. What ensued can be described as (i) a harmonic free-for-all of mismatched tonics, subdominants, and dominants; and (ii) a rhythmic tug-of-war that pitted Watkin’s formulaic handwork against Hooker’s personalised approach. Things would improve slightly over time as, in the words of Neil Slaven (2001, p. 6), ‘[Watkin] more or less adapted himself to the vagaries of Hooker’s performance’. The later recordings show that Hooker also made efforts to reach a stylistic compromise with his bandmates, even if this meant distilling some of the complexities of his groove.

フッカーのブギが、1949年に録音され当初は未発表であった『Do the Boogie』においてピアノ・ブギウギと正面から対峙した際、彼のエレクトリック・ギターは主導的役割を退くことで、様式的な矛盾を回避した。この最初の伴奏付きブギでは、フッカーは主としてヴォーカリスト兼バンドリーダーとして振る舞い、ピアニストのジェームズ・ワトキンとドラマーのカーティス・フォスターが、リズムの推進力の大部分を担っている。同年後半になると、フッカーはインストゥルメンタル曲『609 Boogie』の複数のヴァージョンにおいて、自身のグルーヴを二人の伴奏者のそれと交錯させることを試みた。その結果として生じたのは、(i)主音・下属音・属音が噛み合わないまま入り乱れる、和声的な無秩序状態と、(ii)ワトキンの定型的な手癖とフッカーの個性的なアプローチとがせめぎ合う、リズム上の綱引きであった。ニール・スレイヴン(2001, p.6)の言葉を借りれば、「[ワトキンは]多かれ少なかれフッカーの演奏の気まぐれに自らを適応させていった」ことで、状況は次第に改善していく。後年の録音からは、たとえ自身のグルーヴがもつ複雑さの一部を抽出・簡略化することを意味したとしても、フッカー自身もまた、バンドメンバーとのあいだで様式的な妥協点を見出そうとしていたことがうかがえる。

Accelerating tempos

加速するテンポ

Without exception, Hooker’s tempos are always on the rise. The thrill infused by the boogie’s relentless beat is further heightened by a pervasive accelerando that gradually ups the tempo by anywhere from 6 to 20 metronome points. Even when the recklessness of the opening tempo seems immune to quickening, Hooker still insists on cranking up the pace, as in the 200-to-220 bpm boost of ‘Goin’ Mad Blues’. These unidirectional tempo transformations are not unique to his boogie; they are a universal trait of Hooker’s early recordings, blues included. Admittedly, many performers and styles of music allow for some degree of tempo drift. Perfectly stable tempos can only be the outcome of machine-led renditions, such as those structured around the dictates of a metronome click or drum-machine track. Nonetheless, tempo stability is generally positively valued, since being accused of ‘rushing’ or ‘dragging’ the tempo is as ego-damaging as being told that one’s playing is uninspired or out of tune – the stuff of amateurs. What is particularly striking about Hooker’s accelerandos is their ever-presence, which suggests that they are as fundamental to his musical persona as his stationary harmonies and original strumming patterns.

例外なく、フッカーのテンポは常に上昇していく。ブギの容赦ないビートによってもたらされる高揚感は、テンポを6〜20メトロノーム・ポイントほど徐々に引き上げていく遍在的なアッチェレランドによって、さらに強められる。冒頭テンポの無謀さが、もはや加速の余地を残していないかのように思われる場合でさえ、フッカーはテンポを引き上げることに固執する。たとえば『Goin’ Mad Blues』では、200 bpm から 220 bpm への加速が見られる。この一方向的なテンポ変換は、彼のブギに固有のものではなく、ブルース曲を含むフッカー初期録音全般に共通する特徴である。確かに、多くの演奏家や音楽様式は、ある程度のテンポの揺らぎを許容している。完全に安定したテンポは、メトロノームのクリックやドラムマシンのトラックに従うような、機械主導の演奏においてのみ実現されうる。それでもなお、テンポの安定性は一般に高く評価されており、「走っている」あるいは「もたついている」と非難されることは、演奏が退屈である、あるいは音程が悪いと言われるのと同様に、演奏者の自尊心を大きく傷つける――すなわち、アマチュアの烙印である。フッカーのアッチェレランドにおいて特に際立っているのは、その常在性であり、それは、彼の静的な和声や独創的なストローク・パターンと同様に、音楽的個性の根幹を成していることを示唆している。

Tempo acceleration appears to be an inherent feature of much blues music. David Evans’ blues transcriptions reveal widespread ‘acceleration of the tempo across the course of the performance’ (Evans 1982, p. 45), as do Titon’s (1994) transcriptions of forty-four ‘downhome’ blues. Titon’s sample, which includes recordings made between 1926 and 1930, includes tempos that speed up in magnitudes comparable to John Lee Hooker’s. Other writers have also pointed to specific instances of accelerando in the performances of Robert Johnson: Ford (1998, p. 73) in the second take of ‘Ramblin’ on My Mind’ (‘a tempo that accelerates by a proportion of 5:4 in the third verse’), Boone (2002, p. 64) in ‘Cross Road Blues’ (‘Johnson’s rhythm is similar to [Fred] McDowell’s in its intensity, its regular, swinging beat, and its gradually quickening tempo’), and Backer (2002, p. 120) in Johnson’s overall output (‘The playing is assured; the time is solid although the tempo increases. This has the effect of building excitement as the acceleration is gradual and consistent’). Evans (2000, p. 94) also noticed it in Blind Lemon Jefferson’s ‘Tin Cup Blues’, ‘with the metronome reading fluctuating from qn=98 and qn=106, tending overall to accelerate from the slower to the faster tempo’. And Keil (1966, p. 54) alluded indirectly to this trend, pointing out that as blues music evolved over time, ‘a broader spectrum of tempos is found, and the tempo selected is more rigidly maintained’.

テンポ加速は、多くのブルース音楽に内在する特徴であるように思われる。デイヴィッド・エヴァンスによるブルースの採譜は、演奏の進行に伴う「テンポの加速」が広範に存在することを示している(Evans 1982, p.45)。同様に、Titon(1994)による44曲の「ダウンホーム・ブルース」の採譜にも、それが確認できる。1926年から1930年にかけての録音を含むTitonのサンプルには、ジョン・リー・フッカーに匹敵する規模で加速するテンポが含まれている。他の研究者たちも、ロバート・ジョンソンの演奏における具体的なアッチェレランドの例を指摘している。たとえば、Ford(1998, p.73)は『Ramblin’ on My Mind』の第2テイクにおいて「第3ヴァースで5:4の比率で加速するテンポ」を、Boone(2002, p.64)は『Cross Road Blues』において「その激しさ、規則的でスウィングするビート、そして徐々に速まるテンポにおいて[フレッド]マクダウェルに似たリズム」を、Backer(2002, p.120)はジョンソンの全体的な作品について「演奏は確かで、拍は安定しているがテンポは上昇する。その加速が緩やかで一貫しているため、興奮を高める効果をもつ」と述べている。エヴァンス(2000, p.94)は、ブラインド・レモン・ジェファーソンの『Tin Cup Blues』においても、「メトロノーム値が四分音符=98から106へと変動し、全体として遅いテンポから速いテンポへと加速する傾向」を観察している。また、Keil(1966, p.54)も間接的にこの傾向に言及し、ブルース音楽が時間とともに発展するにつれて、「より広範なテンポのスペクトルが見られるようになり、選択されたテンポはより厳格に維持されるようになった」と指摘している。

To expand this list, we add, in chronological order, four classic recordings that also undergo a tempo increase: Mamie Smith’s ‘Crazy Blues’ (1920, 110–114 bpm), Pine Top Smith’s ‘Pine Top’s Boogie Woogie’ (1928, 166–176 bpm), Muddy Waters’ ‘I Can’t Be Satisfied’ (1948, 196–218 bpm), and Bo Diddley’s ‘I’m A Man’ (1955, 80–86 bpm).

この一覧をさらに拡張するなら、年代順に、テンポ上昇を伴う次の4つの古典的録音を加えることができる。マミー・スミスの『Crazy Blues』(1920年、110–114 bpm)、パイン・トップ・スミスの『Pine Top’s Boogie Woogie』(1928年、166–176 bpm)、マディ・ウォーターズの『I Can’t Be Satisfied』(1948年、196–218 bpm)、そしてボ・ディドリーの『I’m A Man』(1955年、80–86 bpm)である。

Accelerandos have also been noted beyond the realm of the blues. ‘Most black song’, writes Alan Lomax (1993, p. 232), ‘both post- and antebellum, even when its mood is somber and serious when the song begins, usually picks up tempo and is transformed into music that can be danced to before it has been sung to a conclusion’.

アッチェレランドはブルースの領域を超えた音楽にも見いだされている。アラン・ローマックス(1993, p.232)は、「南北戦争後・戦前を問わず、多くの黒人の歌は、たとえ冒頭の雰囲気が陰鬱で深刻であっても、通常はテンポを上げ、歌い終えられる前にダンス可能な音楽へと変貌する」と書いている。

A 1940 report by the Georgia Writing Project’s Savannah Unit describes drum music at a Daddy Grace religious service in the Georgia sea islands: ‘At first the procession is orderly and fairly quiet, but as time passes the music becomes increasingly loud [and] the pulsating rhythm of the instruments increases in tempo’ (quoted in Bastin 1995, p. 158).

1940年のジョージア・ライティング・プロジェクト、サヴァンナ支部の報告書は、ジョージア州シー・アイランズにおけるダディ・グレイスの宗教儀礼での打楽器音楽を次のように描写している。「当初、行列は秩序正しく比較的静かであるが、時間が経つにつれて音楽は次第に大きくなり、楽器の脈動するリズムはテンポを増していく」(Bastin 1995, p.158 より引用)。

Another employee of the Federal Writers Project, folklorist Zora Neale Hurston, describes a prayer ritual at a southern black church: There is in the body of the prayer an accelerando passage where the audience takes no part. It would be like applauding in the middle of a solo at the Metropolitan. It is here that the [preacher] artist comes forth. He adorns the prayer with every sparkle of earth, water and sky, and nobody wants to miss a syllable. He comes down from this height to a slower tempo and is borne up again. (Hurston 1934/1995, pp. 873–4)

連邦作家計画の別の職員であり民俗学者でもあったゾラ・ニール・ハーストンは、南部の黒人教会における祈祷儀礼を次のように描写している。祈りの中には、会衆が一切関与しないアッチェレランドの部分がある。それは、メトロポリタン歌劇場でのソロの最中に拍手をするようなものだ。ここで[説教師という]芸術家が前面に現れる。彼は祈りを、大地、水、空のあらゆる輝きで飾り立て、誰も一音節たりとも聞き逃したくはない。彼はその高みからいったんテンポを落とし、再び持ち上げられるのである(Hurston 1934/1995, pp.873–874)。

Given the foregoing quotes, one is tempted to suspect the accelerando phenomenon to have been a prominent feature of early American black musical culture. But accelerating tempos are also prevalent in numerous musical cultures from around the world, including Native American powwow (Goertzen 2005, p. 289), Hindustani raga (Clayton 2000, p. 88), and the chanted bargaining procedure of Venezuela’s Yanomami Indians (Epstein 1995, p. 344).

以上の引用を踏まえると、アッチェレランド現象は、初期アメリカ黒人音楽文化における顕著な特徴であったのではないかと考えたくなる。しかし、テンポの加速は世界各地の多様な音楽文化にも広く見られる。たとえば、ネイティヴ・アメリカンのパウワウ(Goertzen 2005, p.289)、ヒンドゥスターニー音楽のラーガ(Clayton 2000, p.88)、さらにはベネズエラのヤノマミ族による詠唱を伴う取引儀礼(Epstein 1995, p.344)などが挙げられる。

Why accelerate in the first place? In music, gradual increases seem to be preferable to decreases, as may be observed in other musical parameters besides tempo. For instance, Bach fugues add voices gradually but remove them suddenly (Huron 1990a), and Beethoven’s piano sonatas contain more crescendos than decrescendos, with the former usually lasting longer than the latter (Huron 1990b).

そもそも、なぜ加速するのだろうか。音楽においては、テンポに限らず、徐々に増加する変化は減少よりも好まれる傾向がある。たとえば、バッハのフーガでは声部が徐々に加えられる一方で、突然取り除かれる(Huron 1990a)。また、ベートーヴェンのピアノ・ソナタにはデクレッシェンドよりもクレッシェンドが多く、しかも前者より後者の方が持続時間が長い場合が多い(Huron 1990b)。

In his 1804 Treatise on the Art of Teaching and Practicing the Piano Forte, composer/theorist Daniel Gottlob Türk wrote that ‘in pieces of a fiery, violent, and furious character, the strongest passages must be hastened a little, or played accelerando’ (plate shown in Hudson 1994, p. 123).

1804年の『ピアノフォルテ教授および演奏の技法に関する論考』において、作曲家・理論家のダニエル・ゴットロープ・テュルクは、「激烈で暴力的、そして荒々しい性格の楽曲では、最も強烈な楽節はわずかに急がれるべきであり、すなわちアッチェレランドで演奏されねばならない」と記している(Hudson 1994, p.123 に図版掲載)。

As hinted by Türk’s didacticism, musical tempo correlates with cardiovascular and respiratory rates (Bernardi et al. 2006). Gilbert Rouget, in his book Music and Trance, has noted that trance-inducing music is frequently marked by accelerando and crescendo, and that these processes are linked to the intensification and dramatisation of sound as music reaches a climactic moment (Rouget 1985, p. 84).

テュルクの教訓的記述が示唆するように、音楽テンポは心拍数や呼吸数と相関している(Bernardi ほか 2006)。ジルベール・ルジェは著書『音楽とトランス』において、トランスを誘発する音楽はしばしばアッチェレランドやクレッシェンドを特徴とし、これらの過程が、音楽がクライマックスに達する際の音の強化と劇化に結びついていると指摘している(Rouget 1985, p.84)。

Comparable situations are not unknown in Western concert music. For example, musicologist Reinhard Kopiez and his colleagues (Kopiez et al. 2003, p. 249) noticed a slight tempo increase halfway through a twenty-eight-hour piano performance of Erik Satie’s ‘Vexations’, at which point the pianist reported being in a state of trance.

同様の状況は、西洋のコンサート音楽においても知られている。たとえば、音楽学者ラインハルト・コピエツとその同僚たちは、エリック・サティの『Vexations』を28時間にわたって演奏したピアノ演奏の途中で、わずかなテンポ上昇が生じていることに気づいた。その時点で、演奏者はトランス状態にあったと報告している(Kopiez ほか 2003, p.249)。

A suggestive body of work studying the process of entrainment, the tendency of brainwave patterns to imitate external rhythms – a drum beat, a flashing light – still offers us more questions than answers (Gioia 2006), but the process itself is well known, measurable and repeatable.

外部リズム――ドラムのビートや点滅する光など――を脳波パターンが模倣する傾向、すなわちエントレインメントの過程を研究する示唆的な研究群は、依然として答えよりも多くの疑問を提示しているが(Gioia 2006)、この過程自体はよく知られており、測定可能で再現性もある。

The literature surrounding the ecstatic trances of shamans is especially rich with examples, and it is perhaps revealing that Hooker’s biographer Charles Shaar Murray (2002, p. 371) likens Hooker to a shaman, although Murray seems unaware of the systematic tendency toward tempo acceleration in the blues musician’s work.

シャーマンの恍惚的トランスをめぐる文献には、こうした例がとりわけ豊富に見られる。その点で、フッカーの伝記作家チャールズ・シャー・マレー(2002, p.371)がフッカーをシャーマンになぞらえているのは示唆的である。ただしマレー自身は、このブルース音楽家の作品における体系的なテンポ加速の傾向については認識していないようである。

Housed in these global accelerandos are the three signature rhythmic techniques described above: metric mutations of the isoriff, perceptually distinct upbeats, and blurred temporal order of attacks. The fast tempos, stationary harmonies, and fluid triplet vamps further personalise John Lee Hooker’s now classic groove.

これらの世界的なアッチェレランドの内部には、前述した三つの特徴的なリズム技法――イソリフの拍子的変異、知覚的に際立ったアップビート、そしてアタックの時間順序の曖昧化――が組み込まれている。高速テンポ、静止した和声、流動的なトリプレット・ヴァンプは、ジョン・リー・フッカーの、いまやクラシックと呼ぶべきグルーヴを、さらに個性的なものにしている。

These kinds of rhythmic features – which are so significant in many blues-influenced styles – have been conspicuously neglected in popular music studies. In this light, Hooker’s boogie of the late 1940s presents a rich case study of rhythmic expressivity during a pivotal moment in American popular music.

こうしたリズム的特徴は、多くのブルース影響下の様式においてきわめて重要であるにもかかわらず、ポピュラー音楽研究においては目立って看過されてきた。その意味で、1940年代後半のフッカーのブギは、アメリカ大衆音楽の転換点におけるリズム表現性を考察するための、きわめて豊かなケーススタディを提供している。

Endnotes

- Definitions of what constitutes a ‘hook’ vary.

The nature of rhythmic hooks is examined in Traut (2005). - David Evans and Gayle Dean Wardlow (personal communication) confirmed that Will Moore was virtually unknown in the Clarksdale scene. Evans notes, however, that Hooker’s style bears some resemblance to the little-known work of Country Jim Bledsoe and Clarence London, guitarists who were recorded in Shreveport, Louisiana in the early 1950s. Since we know that Moore hailed originally from Shreveport, we can speculate that Hooker’s approach may reflect a regional style centred in Shreveport that his step-father brought with him to the Clarksdale area. However, our present knowledge of the early Shreveport blues tradition is limited, although this could present an interesting area of research for later scholars.

- The exceptions are all post-1951. The tempo of ‘That’s Alright’ is 114–118 bpm; it is the result of a duo session led not by Hooker but by his musical sidekick Eddie Kirkland in 1952. ‘Too Much Boogie’ (1953) drags in reminiscing slow motion at 112 bpm. By 1954, tempos in the 120s would not be uncommon, especially in accompanied numbers such as ‘I’m Ready’ (126–129 bpm) and ‘Hug and Squeeze’ (120–123 bpm).

- Some songs, such as ‘Don’t Go Baby’, have a boogie tempo and a stomping foot, but their character is more contemplative than rambunctious. A couple of others, such as ‘Low Down Boogie’, are really slow blues despite their title.

- We agree with ‘the apparent four-ness of 12/8’ (Agawu 2006, p. 21, note 42). Hence, when discussing ternary subdivisions of the beat, we consciously interchange the concepts of 4/4 triplet quavers and 12/8 quavers.

- Clearly, neither the duple nor triple subdivisions receive metronomic treatment.

- Examples include ‘I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom’, ‘Honeymoon Blues’, ‘Kind Hearted Woman Blues’, and ‘Ramblin’ On My Mind’.

- Pianists did not face the same challenge as guitarists. For an example of triplet-quaver isoriffs at a boogie tempo, listen to ‘Do the Boogie’ (1:33–1:41). At 200 bpm, James Watkin manages to articulate the isoriff at a tremolo-like rate of ten attacks per second.

- Millisecond values do not correspond to exact measurements of the audio signal. Rather, they are calculated arithmetically based on the song’s approximate tempo. For example, a quaver is 200 ms long at a tempo of 150 bpm, although the actual durations as performed will be naturally higher and lower.

- Cohen (1996, p. 465) also describes the ‘t-1 run’, a technique whereby the thumb and index finger alternate attacks on a single string, like a plectrum, to play scalar passages. This technique was more prevalent in the East than in the Delta. Although Cohen is careful to note that players are likely to employ more than one approach to hand posture and fingerpicking, he maintains that these physical aspects are closely intertwined with regional styles.

- A milder form of this effect was noted by Titon (1994, p. 146): ‘When the syncopation is continuous, the natural result is a conflict of pulse patterns (polyrhythm) between the vocal and the accompaniment’. But such instances last no longer ‘than two and a half beats’—a stark contrast to Hooker’s perennial syncopation.

- In some instances, the poor quality of the acetate recordings results in a gradual fall in pitch—and a (uncharacteristically) steady tempo. For instance, the ‘Stomp Boogie’ tempo of 164 bpm undergoes a negligible increase of two points, while the pitch drops by about 75 cents. Restoring the ending pitch (by ear) to match that of the beginning reveals that the song originally accelerated to 172 bpm. Similar re-enactments of otherwise tempo-static performances reveal comparable tempo changes (170–178 and 190–202 bpm, respectively).

- This is not a gradual accelerando; the tempo changes rather abruptly towards the end of the song.

- But on the other side of that hit record, ‘I Feel Like Going Home’ maintains the tempo constant at 78–79 bpm.

- Hooker’s accelerando resembles two of the four types distinguished by Clayton (2000, pp. 88–9) in Hindustani music:

‘(a) Gradual and slight, and perhaps unintentional’ and

‘(b) Gradual but significant; resulting in increased tension and excitement’.

(The other two are ‘(c) Stepwise; a conscious acceleration at a particular point in a performance’ and ‘(d) Temporary; for example to serve the needs of a tabla solo’.) - More recently, composers as diverse as Conlon Nancarrow (Gann 1995, pp. 146–72) and John Adams (Adams et al., pp. 96–7) have often used gradual accelerandos to animate the musical surface.

References

Adams, J., Jemian, R., and de Zeeuw, A. M. 1996.

‘An interview with John Adams’, Perspectives of New Music, 34/2, pp. 88–104.

Agawu, K. 2006.

‘Structural analysis or cultural analysis? Competing perspectives on the “standard pattern” of West African rhythm’, Journal of the American Musicological Society, 59/1, pp. 1–46.

Backer, M. 2002.

‘The Guitar’, in The Cambridge Companion to Blues and Gospel Music, ed. A. Moore (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press), pp. 116–129.

Bastin, B. 1995.

Red River Blues: The Blues Tradition in the Southeast (Urbana, IL, Illini Books).

Benadon, F. 2006.

‘Slicing the beat: jazz eighth-notes as expressive microrhythm’, Ethnomusicology, 50/1, pp. 73–98.

—— 2007.

‘A circular plot for rhythm visualization and analysis’, Music Theory Online, 13/3.

Bernardi, L., Porta, C., and Sleight, P. 2006.

‘Cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and respiratory changes induced by different types of music in musicians and non-musicians: the importance of silence’, Heart, 92, pp. 445–452.

Boone, G. M. 2002.

‘Twelve Key Recordings’, in The Cambridge Companion to Blues and Gospel Music, ed. A. Moore (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press), pp. 61–88.

Bregman, A. 1990.

Auditory Scene Analysis (Cambridge, MA, MIT Press).

Bregman, A., and Campbell, J. 1971.

‘Primary auditory stream segregation and perception of order in rapid sequences of tones’, Journal of Experimental Psychology, 89, pp. 244–249.

Clayton, M. 2000.

Time in Indian Music: Rhythm, Metre, and Form in North Indian Rag Performance (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

Cohen, A. M. 1996.

‘The hands of blues guitarists’, American Music, 14/4, pp. 455–479.

Collier, G., and Wright, C. E. 1995.

‘Temporal rescaling of simple and complex ratios in rhythmic tapping’, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance, 21/3, pp. 602–627.

Davis, F. 1995.

The History of the Blues (New York, NY, Da Capo Press).

Ellis, A. 2005.

‘How to play like John Lee Hooker’, Guitar Player, January, p. 110.

Epstein, D. 1995.

Shaping Time: Music, the Brain, and Performance (New York, NY, Wadsworth Publishing).

Evans, D. 1982.

Big Road Blues: Tradition and Creativity in the Folk Blues (Berkeley, CA, Da Capo Press).

—— 2000.

‘Musical innovation in the blues of Blind Lemon Jefferson’, Black Music Research Journal, 20/1, pp. 83–116.

Ford, C. 1998.

‘Robert Johnson’s rhythms’, Popular Music, 17/1, pp. 71–93.

Friberg, A., and Sundström, A. 2002.

‘Swing ratios and ensemble timing in jazz performance: evidence for a common rhythmic pattern’, Music Perception, 19/3, pp. 333–349.

Gann, K. 1995.

The Music of Conlon Nancarrow (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press).

Gioia, T. 2006.

Healing Songs (Durham, NC, Duke University Press).

Goertzen, C. 2005.

‘Purposes of North Carolina Powwows’, in Powwow, ed. C. Ellis, L. E. Lassiter, and G. H. Dunham (Lincoln, NE, Bison Books), pp. 275–302.

Hirsh, I. J., and Sherrick, C. E. 1961.

‘Perceived order in different sense modalities’, Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62, pp. 423–432.

Hudson, R. 1994.

Stolen Time: The History of Tempo Rubato (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

Huron, D. 1990a.

‘Increment/decrement asymmetries in polyphonic sonorities’, Music Perception, 7/4, pp. 385–394.

—— 1990b.

‘Crescendo/diminuendo asymmetries in Beethoven’s piano sonatas’, Music Perception, 7/4, pp. 395–402.

Hurston, Z. N. 1934/1995.

‘Spirituals and Neo-Spirituals’, in Folklore, Memoirs, and Other Writings, ed. C. Wall (New York, NY, Library of America), pp. 869–874.

Iyer, V. 2002.

‘Embodied mind, situated cognition, and expressive microtiming in African-American music’, Music Perception, 19/3, pp. 387–414.

Keil, C. 1966.

Urban Blues (Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press).

Kopiez, R., Bangert, M., and Altenmüller, E. 2003.

‘Tempo and loudness analysis of a continuous 28-hour performance of Erik Satie’s composition “Vexations”’, Journal of New Music Research, 32/3, pp. 243–258.

Koransky, J. 2001.

‘Boogie endin’: John Lee Hooker: 1917–2001’, DownBeat, 68/9, pp. 16–17.

Kubik, G. 1999.

Africa and the Blues (Jackson, MI, University Press of Mississippi).

LeBlanc, A., Colman, J., McCrary, J., Sherrill, C., and Malin, S. 1988.

‘Tempo preferences of different age music listeners’, Journal of Research in Music Education, 36/3, pp. 156–168.

Lomax, A. 1993.

The Land Where the Blues Began (New York, NY, Pantheon Books).

London, J. 2004.

Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter (Oxford, Oxford University Press).

Moore, B. 2003.

An Introduction to the Psychology of Hearing (San Diego, CA, Academic Press).

Moore, B., and Gockel, H. 2002.

‘Factors influencing sequential stream segregation’, Acta Acustica Acustica, 88, pp. 320–332.

Murray, C. S. 2002.

Boogie Man: The Adventures of John Lee Hooker in the American Twentieth Century (New York, NY, St. Martin’s Griffin).

Oakley, G. 1997.

The Devil’s Music: A History of the Blues (New York, NY, Da Capo Press).

O’Neal, J., and van Singel, A. 2002.

The Voice of the Blues: Classic Interviews from Living Blues Magazine (New York, NY, Routledge).

Rouget, G. 1985.

Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations Between Music and Possession, trans. B. Biebuyck (Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press).

Slaven, N. 2001.

Liner notes to The Complete John Lee Hooker, Detroit 1949–1950, Body & Soul 3067872.

Stewart, A. 2000.

‘“Funky drummer”: New Orleans, James Brown and the rhythmic transformation of American popular music’, Popular Music, 19/3, pp. 293–318.

Titon, J. T. 1994.

Early Downhome Blues (Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Press).

Traut, D. 2005.

‘“Simply irresistible”: recurring accent patterns as hooks in mainstream 1980s music’, Popular Music, 24/1, pp. 57–77.

Discography

John Lee Hooker, The Complete John Lee Hooker.

Body & Soul:

Vol. 1: Detroit 1948–49, 3057012, 2000.

Vol. 2: Detroit 1949, 3063142, 2000.

Vol. 3: Detroit 1949–50, 3067872, 2001.

Vol. 4: Detroit 1950–51, 3074242, 2003.

Vol. 5: Detroit 1951–53, BS 2500, 2004.

Vol. 6: Detroit/Miami 1953–54, BS 2653, 2005.